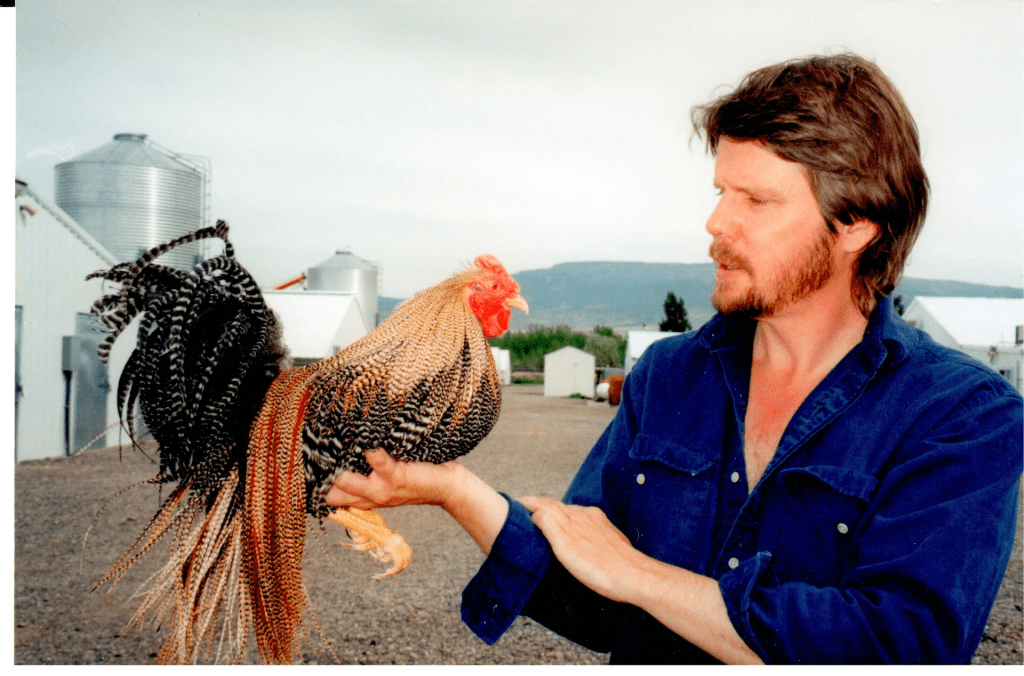

Genetic hackle breeding by Whiting, Metz, Keough, and their predecessors has given fly tyers the gift of perfect feathers—albeit at a steep price. There is no doubt that you get what you pay for when you pick that $100 rooster saddle off the rack at the local fly shop. However, we are definitely spoiled for choice when it comes to feather selection, often at the cost of our sanity. There are too many options on the shelves, and it’s easy to get lost in the noise. I know I do. Hopefully, I can lend some insight into the purpose each category of pelt serves.

Please note that I am only covering chicken pelts. The list of gamebirds and waterfowl available to fly tyers is exhaustive and would involve writing a book on genetic feather breeding—an ordeal I am not willing to undertake. Enjoy this simple guide written by a simple guy.

A Word on Semantics

Capes come from the bird’s neck and are often referred to as necks, depending on the manufacturer. Saddles come from the portion of the back closest to the tail. If you visualize where a saddle is placed on a horse, you’re on the right track. Spey hackle comes from the rearmost portion of the saddle, where it joins the tail. Spade hackle comes from where the neck meets the saddle.

Rooster Saddles

Rooster saddles have long been prized for their use in dry flies. Selective breeding over many decades has yielded long, narrow feathers suitable for even the smallest dry flies, depending on the grade. Higher grades are longer, more uniform, and tend to have narrow tapers. Rooster saddles bred for dry flies also feature dense barbs to increase fiber density per wrap.

When buying saddles, note that the feathers tend to be fairly uniform in size, usually spanning only three sizes of dry fly. You’ll need to be certain of the size you’re purchasing and plan on tying hundreds of the same size flies for years to come. For many, this isn’t an issue. For the economical tyer, I’d generally steer clear. Non-commercial tyers are often better served buying saddles by the half-saddle.

Rooster Capes/Necks

Rooster capes are very versatile for the budget tyer. One cape can yield hundreds of feathers suitable for dry flies ranging from sizes 6–22 while also providing excellent material for streamer patterns. In fact, the more rounded profile of cape feathers has proven its worth as a premier choice for streamer tyers in both fresh and saltwater. The stems are strong and less likely to break when chomped by a big, toothy fish.

Rooster capes have stiffer fibers than hen capes. They work great when palmered on flies intended for bigger, pushier water. The spade hackle at the bottom of the cape especially resists current that would collapse fibers on most flies. They also do a decent job propping up softer materials such as ostrich or marabou.

Hen Saddles

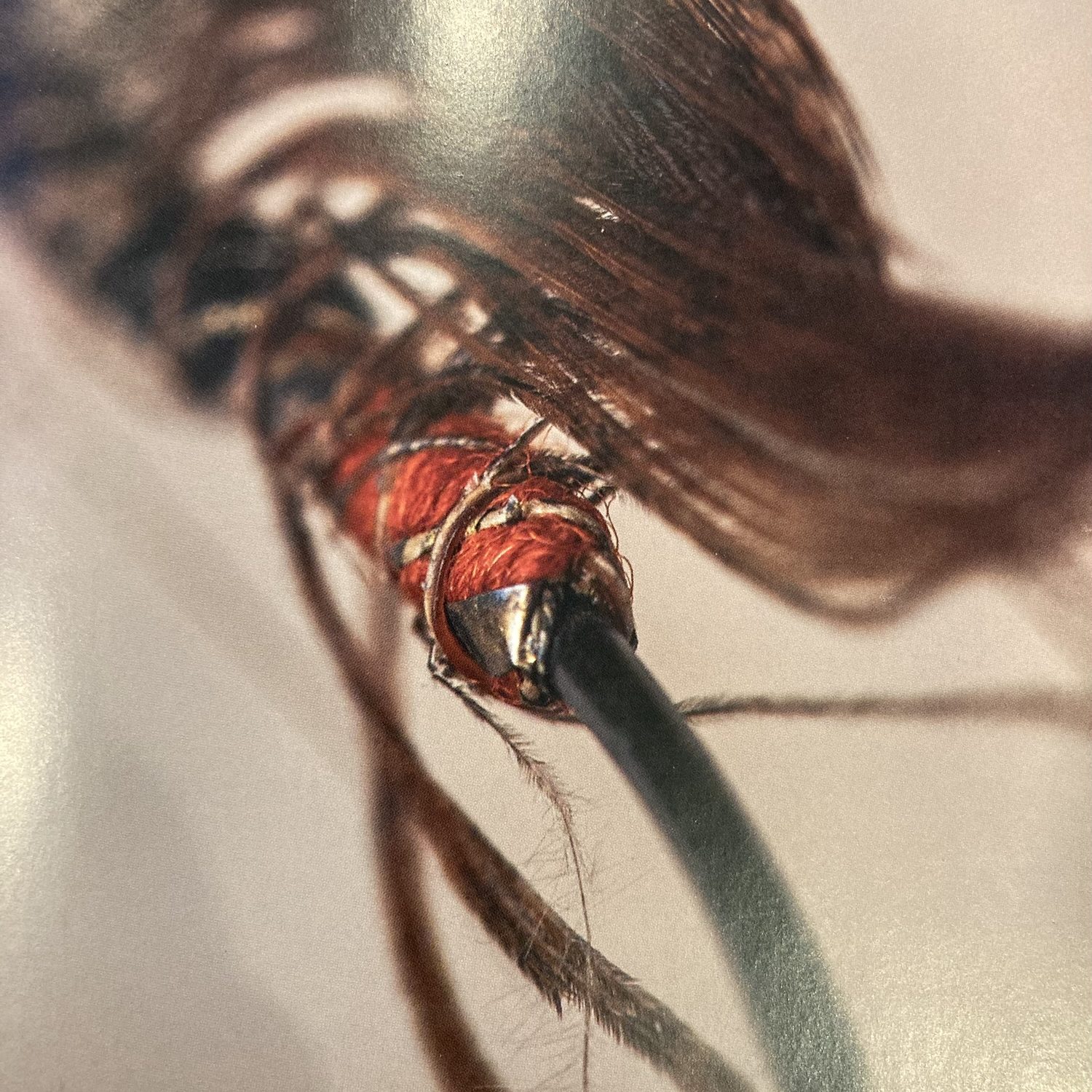

Hen saddles feature long, large feathers with rounded tips. These feathers are much softer than rooster saddle hackle and give flies a full, lifelike appearance. Because of their size and flowy texture, they make excellent collars for steelhead and salmon wet flies. However, like rooster saddles, they have limited size variation, so choose a saddle that fits most of the flies you plan to tie. I’ve noticed that these feathers can be on the webby side depending on their location on the saddle.

Hen Capes/Necks

Hen capes offer long, narrow, soft feathers with a wide range of sizes, making them extremely versatile. Smaller feathers work well for hackled collars on small wet flies and nymphs. The soft tips of the narrowest feathers are ideal for feather-winged dry flies. Longer feathers are well suited for streamers with flowing freshwater tails. This may be the best choice for the budget tyer looking to maximize value from their first full skin.

Hen cape fibers are soft and supple, making them best suited for slower water. Fast, pushy Western rivers will collapse the fibers along the body of the fly, so fish them in softer seams and slower runs to maximize their pulsating effect.

Deciphering the Patterns

Let’s keep this simple:

- Barring = black stripes on the feather

- Grizzly = barred black and white (often dyed various colors, such as chartreuse)

- Speckling/Mottling = fine dark markings distributed throughout the feather

- Badger = a dark line running the length of the feather

- Variant = colors and patterns vary throughout the pelt

A Couple of Lingering Feather Types

You may also find a few specialty feathers on a pelt:

- Marabou = fluffy, flowing feathers with a relatively thick stem; commonly used for tails and full collars

- Chickabou = smaller, finer, more delicate marabou

- Schlappen = very webby hackle whose fibers tend to clump rather than distribute evenly when palmered

So, What Should I Buy?

The average tyer should invest in high-quality rooster and hen capes. Saddles tend to serve more specific purposes and sizes, so I’d avoid them if versatility is your goal. A well-rounded collection might include several cape colors in a variety of patterns.

Buying white pelts in different patterns allows you to dye your own feathers and save money. I haven’t tried it myself yet, but it sounds like a fun future article. At the end of the day, your pelt collection should reflect your tying style and the flies you enjoy most. If you tie size 18 PMDs all day, then get the rooster saddle that fits the job. For the rest of us, start collecting capes.That’s all for now.

– T